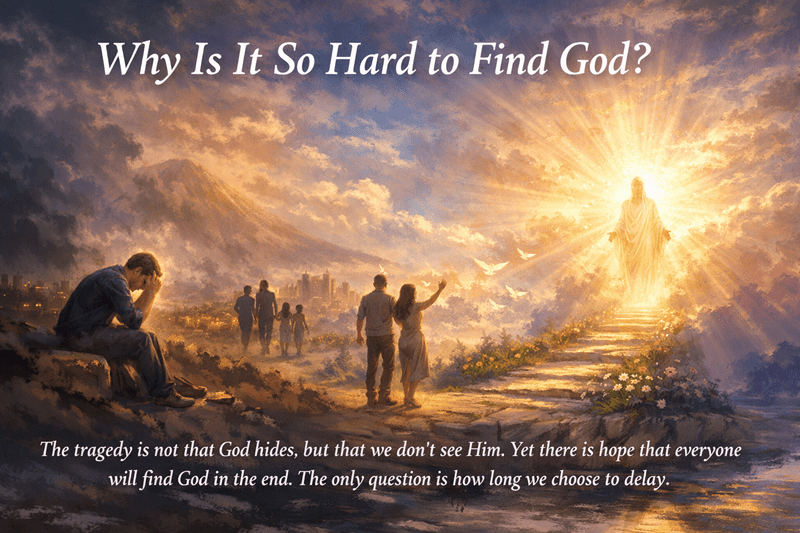

Why is it so hard to find God? Because we do not yet desire Him above all else. OSWALD PEREIRA presents Paramahansa Yogananda’s views on the subject. The tragedy is not that God hides, but that we don’t see Him. Yet there is hope that everyone will find God in the end. The only question is how long we choose to delay.

The great sage and yogi Paramahansa Yogananda once posed a question that has haunted seekers across civilizations: Why is it so hard to find God?

The question is ancient. The answer, he suggests, is simple.

As I read Yogananda’s reflections, I am struck not by mysticism alone, but by moral clarity. He does not blame fate, nor theology, nor the silence of heaven. He places responsibility squarely upon us. We long for God, he says—but we do not seek Him with sufficient depth. We knock, but not long enough. We pray, but without surrender. We meditate, but with one eye still open to the world.

God, according to Yogananda, gives to us exactly what we give to Him. No more. No less.

There is a story he narrates of an Indian saint whose body was ravaged by disease. The saint did not ask for healing. He prayed instead, “Lord, come into this broken temple.” Eighteen hours a day he meditated. Months passed. One day he declared he had found God—and his body, he said, was restored.

The beauty of that prayer lies in its inversion. He did not seek the gift; he sought the Giver. The healing, if it came, was incidental. The transformation was inward.

This is consistent with what sages across traditions have taught. Sri Ramakrishna would say that God reveals Himself when the devotee weeps for Him as intensely as a drowning man gasps for air. Swami Vivekananda thundered that religion is not talk, nor doctrine, but realisation. Saint Augustine confessed centuries earlier: “Our hearts are restless until they rest in Thee.”

Yogananda’s point is not theological—it is psychological and spiritual. The mind, he says, is like a window. Pull down the shades, and sunlight cannot enter. Open it, and illumination floods in. We complain of darkness, yet we draw the curtains ourselves.

How often do we truly examine our inner life? If we are honest, we will discover how little time we devote to silence. Two hours of daily meditation, Yogananda suggests, can transform a life. It is not ritual that changes us; it is sustained interior discipline.

Here he echoes the Bhagavad Gita’s call to detachment and concentration. The mind, left untended, wanders like a restless child. Anchored in meditation, it becomes a channel for grace.

Yogananda uses a simple agricultural metaphor: the growth of a plant requires both soil and seed. In spiritual life, the seed is preparation—the inner conviction that God can indeed be realised. If one secretly believes, “I shall never find Him,” that doubt becomes self-fulfilling. But if devotion is sincere, he says, the soul plunges deep, like a diver reaching the ocean floor.

There is something profoundly democratic in this teaching. No guru can hand you enlightenment. No priest can confer it as a certificate. “You have to work hard to reach the Infinite,” he insists. Even the greatest teachers cannot grant Self-realisation unless the seeker labours for it.

This emphasis on effort aligns him with spiritual reformers everywhere. Gautama Buddha urged his disciples to “be a lamp unto yourselves.” Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote that nothing can bring you peace but yourself. The path, in every tradition, demands participation.

Yogananda also speaks of affirmations—prayers charged not merely with words, but with feeling. A thought, when deeply impressed upon the mind, sinks from the conscious to the subconscious, and finally into what he calls the superconscious. There it bears fruit in life. This anticipates modern psychology’s understanding of the power of conviction, but Yogananda roots it in spiritual science.

Above all, he insists that the greatest healing we should seek is the healing of ignorance. Physical ailments, social struggles, even emotional wounds—these are secondary. The fundamental malady is forgetfulness of our divine origin.

His closing prayer is not sectarian. It is universal. He asks that we see, hear, think, and touch only what is good; that we recognise God as the sovereign of our ambitions; that we awaken divine love in all hearts.

In essence, Yogananda is telling us that God is not absent. We are distracted.

We chase shadows and then lament the darkness. We pray for outcomes, not for union. We seek comfort, not transformation. And when the effort becomes demanding, we retreat.

Why is it hard to find God? Because we do not yet desire Him above all else.

The tragedy is not that God hides. The tragedy is that we don’t see Him.

Yet there is hope in Yogananda’s assurance: everyone will find God in the end. The only question is how long we choose to delay.